|

PAUL MORPHY: HIS

LATER LIFE

BY C. A. BUCK.

WILL. H. LYONS,

NEWPORT, KENTUCKY.

JANUARY, 1902.

PUBLISHERS

PREFACE

C.

A. Buck of Toronto, Kansas is the author of this interesting and comprehensive

biography of Paul Morphy.

Mr. Buck has gathered from authentic sources facts and data in the

later life of Morphy that have never been published, Several years were devoted

to securing information; a month was then spent in New Orleans verifying and

adding to his store of facts; Morphy's relatives and friends giving him great

assistance. The matter first appeared in a prominent Western newspaper. With Mr.

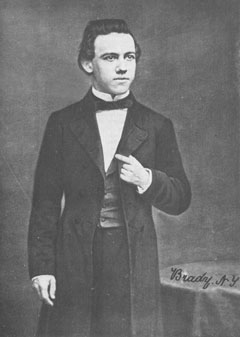

Buck's consent, I now offer it in its present form. I have added a portrait of

Mr. Morphy from a photograph taken immediately after his return from Europe,

also his autograph.

WILL H. LYONS.

PAUL MORPHY

The

chronicles of Chess, amplified as it is by a literature richer than that of any

other game, offer to the student nothing to compare with the career of Paul

Morphy, the game's greatest master. A number of circumstances conspire to make

Paul Morphy an unique and monumental character in chess history. The two salient

factors of his fame were, of course, his wonderful chess play and of his extreme

youth during the period of his active chess career. Incidentally, the fact that

he was the only master of the first class that America had produced up to his

time augmented his prestige; and then, too, his personality, marked as it was by

many graces of the mind, added lustre to his fame. His later life, during which

he met with many disappointments and reverses, finally resulting in a mild form

of mania, adds a melancholy interest to his career. It was such a contrast to

what his youth gave promise of that it seems almost tragic in its aspects. The

chronicles of Chess, amplified as it is by a literature richer than that of any

other game, offer to the student nothing to compare with the career of Paul

Morphy, the game's greatest master. A number of circumstances conspire to make

Paul Morphy an unique and monumental character in chess history. The two salient

factors of his fame were, of course, his wonderful chess play and of his extreme

youth during the period of his active chess career. Incidentally, the fact that

he was the only master of the first class that America had produced up to his

time augmented his prestige; and then, too, his personality, marked as it was by

many graces of the mind, added lustre to his fame. His later life, during which

he met with many disappointments and reverses, finally resulting in a mild form

of mania, adds a melancholy interest to his career. It was such a contrast to

what his youth gave promise of that it seems almost tragic in its aspects.

It is curious to note that

while the name of Paul Morphy is known wherever chess is played, and most every

practitioner of the game is familiar with his chess, yet there are few players

of to-day who know of his later life, dating from his return from Europe in

1859. A sketch of Morphy's later life, however brief and fragmentary, should

properly be prefaced by a review of his chess career, not only in the interest

of a harmonious whole, but that the reader may have a better understanding of

some phases of his character that developed with the maturity of years.

Paul Morphy was born in New Orleans, June 22, 1837. He learned

chess at the age of ten, graduated at Spring Hill college, near Mobile, Ala., in

1854, studied law and was admitted to the bar in April, 1857. He was gifted with

a wonderful mind, its precocious powers being revealed not only in chess but in

his studies as well. It should be noticed that before he was twenty years old he

had graduated at college and at a law school, his learning embracing fluency in

four languages and ability to recite from memory nearly the entire Civil Code of

Louisiana. Morphy's chess practice during his childhood was

mainly with his father and his uncle, Ernest Morphy. He gave evidence of a keen

aptitude for the game and was soon able to defeat them both, although his uncle

especially was a strong player. His natural capacity for chess was shown in his

seeming divination of the proper moves in the openings before he had ever

studied them.

Ernest Morphy wrote to Kieseritzky in October, 1849, that his nephew, then a

little over twelve years old, had never opened a chess treatise but that "in the

openings he plays the 'coups justes' as if by inspiration." As a matter

of fact, Morphy did not at any time have the benefit of chess books in the sense

of keeping a number of them at hand for study and reference. What few books he

made use of he went through quickly as possible, and after having mastered the

contents he gave them away. James McConnell, the elder, of New Orleans, has a

book of the tournament of 1851 which Morphy gave him when fifteen years old. The

book had been issued but a short time when Morphy secured this copy. He soon

played over all the games and then gave it to his friend. The volume is

especially interesting on account of numerous marginal notes in Morphy's own

handwriting by which he expressed his opinion of the games and certain moves. As

is well known, this book was edited by Staunton, and young Morphy, like a child

of genius, made a captious comment on Staunton's chess play by writing on the

title page to make the authorship read like this: "By H. Staunton, Esq., author

of the Hand-book of Chess, Chess-Player's Companion, etc. (and some devilish bad

games)."

Paul Morphy first showed the genius of a coming master in the three games he

played with Löwenthal, the distinguished Hungarian player, in May, 1850, when he

was not quite thirteen years old. Of these games he won two and drew the other.

His encounters, about this time, with Eugene Rousseau, a native of France but

then a resident of New Orleans, further showed a surpassing mastery of chess for

a boy just entering his teens. Rousseau's rating as a chess player may be judged

by the games he played with Kieseritzky on even terms, of which there were more

than one hundred, the latter winning a bare majority. Morphy and Rousseau played

over fifty games during the years 1849 and 1850, and Morphy won nine-tenths of

them.

Regarding the games with Löwenthal, it is a curious circumstance that

five years after Morphy's death there appeared in the Chess Review of Havana an

apocryphal game wherein Morphy accepted the odds of pawn and move, the claim

being made that the game was the third one of the series played with Löwenthal

in 1850. The game had previously been submitted to no less a chess scholar than

Max Lange who pronounced it genuine. There were several things, so it was

claimed, that clothed this bogus game with verisimilitude, chiefly the fact that

of three games played the scores of only two were preserved. Fortunately,

however for Morphy's reputation, Charles A. Maurian, than whom no one is better

qualified to pass an opinion on anything pertaining to Morphy, has proved that

Morphy did not accept odds on that occasion. The claim, notwithstanding Max

Lange's support of it, has been utterly exploded.

From his thirteenth to his twentieth year Morphy was devoted to his

studies, but during his vacations, which were spent for the most part at home in

New Orleans, he played chess with the strong amateurs of the city and with such

players of force who were sojourning there. Hence, when the first American chess

congress convened in New York in October, 1857, his renown as a chess player had

preceded him and he was the cynosure of the chess enthusiasts. He won the first

prize in this event, and after the tournament he issued a challenge to play a

match with any New York player and yield the odds of pawn and move. This was

accepted by C. H. Stanley, who was one of the foremost players of his time,

having defeated Rousseau in a match by a score of 15 to 8. The proposed match

was for seven games up, but Stanley resigned after five games had been played,

Morphy winning four and Stanley one. This challenge at the odds of pawn and move

was also leveled at James Thompson, a player of some force, who participated in

the main tournament of the congress. Morphy and Thompson had played as many as

eight games together on even terms, including the games in the tournament, and

Morphy had won all of them, yet Thompson was not prepared to admit that the

disparity of pawn and move existed between them. As Thompson would not accept

the odds in casual play Morphy sought to tempt him with the odds in a match.

Referring to this matter in a letter home at the time Morphy observes that "he

seems to fancy that it is beneath his dignity to accept odds of a player who has

won every game contested with him. My impression is that I can give him the odds

and make even games." But Thompson did not accept the challenge. Attention is

called to the chess vanity that prevented Thompson from playing Morphy and take

the odds of pawn and move, because after Morphy's return from Europe eighteen

months later he defeated Thompson decisively at the odds of a knight ! Winning

this match at such odds against a player of Thompson's ability is regarded by

some as Morphy's greatest achievement.

Before leaving New York

Morphy amended his challenge to the New York players to embrace any player in

America. The effect of this was to offer the odds of pawn and move to Louis

Paulsen of Iowa, the second prize winner of the congress - a player who, like

Morphy, made his first appearance before the chess world at this congress, and

who, with Morphy eliminated, would have been the most conspicuous player there.

No result came of the challenge however.

Morphy went to England in

June, 1858, to play Staunton, the representative of English chess, but failed to

meet him in a match owing to default by Staunton. They did meet however, in

consultation play, Morphy's ally being Thomas Wilson Barnes and Staunton's

confrere being Rev. J. Owen ("Alter" in chess circles). Two games were played,

and Morphy and Barnes won both. Morphy played a match with Löwenthal, and won by

a score of nine games to three, with two draws; also a match with Rev. J. Owen,

at odds of pawn and move, winning five games and losing none, with two draws. In

France he played three matches, winning against Anderssen, 7 to 2, and two

draws; against Harrwitz 5 to 2, and one draw; Mongredien 7 to o. While in Europe

Morphy gave four séances in blindfold play, at Birmingham, at the London Chess

club, at the St. George's Chess club (London), and at Paris. In each contest he

played eight games, and made the unique record of losing only one game, although

several were drawn, six by agreement. His performance at Paris, considering the

strength of his adversaries, is held by some critics to be the crowning

achievement in blindfold play. Morphy never regarded this form of chess

seriously ; he remarked one time that "it proves nothing." He held to the

opinion that a player's strength was measured by his play against single

adversary across the board.

After his sojourn in Paris,

Morphy returned to London and played many informal games with the strongest

English players, notably with S. S. Boden and Thomas Wilson Barnes. Morphy

regarded Mr. Boden as the strongest English player.

The consensus of opinion

seems to be that Morphy's chief claim to preeminence in chess rests upon his

victory over Anderssen, winner of the world's tournament in London in 1851, and

admittedly the best player in Europe. In addition to the match games, Morphy and

Anderssen played six informal games, of which the Prussian master scored only

one. The informal and match games made a total of seventeen games played by

these masters, of which Morphy won twelve, and Anderssen three, and two were

drawn. Such a result was so overwhelming as to cause consternation in European

chess circles, and the chess writers of the time sought to sustain the shattered

prestige of their master by explaining that Anderssen was in poor health and out

of practice at the time. As to the question of practice, Anderssen himself felt

that he could play good enough to win the match, and as to his health, he was

well enough to travel from Breslau to Paris in order to play. On the other hand,

Morphy had been ill in bed for several weeks before the match, was still

confined to his bed when Anderssen arrived, and was unable to sit up for several

days thereafter. His physician finally permitted him to play the match in the

hotel and thus avoid the fatigue incident to playing in public at the Café de la

Régence.

It was while in Paris, during the month of December, 1858, that Morphy's

so-called aversion to chess began to manifest itself, and his feelings in this

particular became so aggravated in later years as to create the general belief

that he grew to positively dislike the game. This is a mistake. His experience

in European chess circles was a revelation to him. It should be remembered that

he was a boy, inspired by the ardor, enthusiasm and high ideals of youth ; and

loving chess as he did, he was shocked and disgusted at the sordid

conventionalities of chess practice that was in vogue. The taint of

professionalism was repellant to him, and when he saw how the game was made a

business of, his disgust led him to forsake the haunts of chess. Morphy's idea

regarding the morals of chess is not suggested for the purpose of making any

invidious comparisons, but simply to establish the fact that it was not chess

that he grew to dislike, but the practice of it by those who would make a living

by it. As Morphy was fated to be in a way an involuntary victim of his fame as a

chess player, his ideas in this respect are important as explaining a peculiar

phase of his character.

Morphy returned to America in May, 1859, and was

greeted with all the enthusiasm due a conquering hero. In the presence of a vast

assembly in the chapel of the University of New York he was presented with a

testimonial in the shape of a magnificent set of gold and silver chess men, with

board to match, the most costly, perhaps, that were ever wrought. The

festivities of this occasion were unhappily marred by a dramatic episode that

showed Morphy's growing sensitiveness to the "profession of chess." Colonel

Charles D. Mead, president of the American Chess association, was chairman of

the reception committee which greeted Morphy, and in his address of welcome he

made an allusion to chess as a profession, and referred to Morphy as its most

brilliant exponent.

Morphy took

exception to being characterized as a professional player, even by implication,

and he resented it in such a way as to overwhelm Colonel Mead with confusion.

Such was his mortification at this untoward event that Colonel Mead withdrew

from farther participation in the Morphy demonstration. The Union Chess club of

New York presented Morphy with a superb sterling silver wreath as a token of

victory over all, In Boston, also, Morphy was given a banquet, at which

Longfellow, Holmes, Lowell, Agassiz and many others eminent citizens were

present to tender him their congratulations.

So great an interest did Morphy's achievements create in chess in

this country that Robert Bonner, the enterprising publisher of the New York

Ledger, started a chess column in his paper, and secured for it at once

widespread popularity by engaging Morphy as chess editor at a salary of $3,ooo a

year, paid in advance. The feature of the Ledger column was the

publication of about fifteen of the games between De La Bourdonnais and

MacDonnell, annotated by Morphy. Morphy intended to publish all the games

between these two masters, as he considered them the finest specimens of chess

on record.

Shortly after reaching New Orleans Morphy issued a final challenge,

offering to give the odds of pawn and move to any player in the world, and

receiving no response thereto he declared his career as a chess player finally

and definitely closed, a declaration to which he held with unbroken resolution

during the whole remainder of his life.

Morphy made arrangements to practice law soon after his return to

his native city, but his fame as a chess player was so over shadowing that it

seemed people were disinclined to regard him seriously in any other capacity.

His fellow citizens looked upon him simply as a marvelous chess player and

nothing more, and this so irritated him that he began to have an aversion to

playing the game even privately. In fact, he became so morbid on the effect of

chess on his career as a lawyer that, in spite of all the efforts of his friends

and relatives, he gave up the work of chess editor of the Ledger, and the

contract for which he had been engaged was completed by W. J. A. Fuller. Morphy

was associated with D. W. Fiske in the publication of the American Chess

Monthly, and although his name was carried on the publication as one of its

editors during the five years of its existence (1857-1861) it is known that he

did very little of the work.

An incident may here be related as showing how Morphy was often crucified

on the cross of his fame. He became enamored of a wealthy and handsome young

lady in New Orleans and informed a mutual friend of the fact, who broached the

subject to the lady, but she scorned the idea of marrying a "mere chess player,"

Small wonder that he became morbid and abjured the practice of chess.

During the year 1861 Morphy visited Richmond, Va., seeking to

obtain an appointment in the diplomatic service of the southern confederacy, but

he did not succeed and returned to New Orleans. He was there when the city was

captured by the federal forces. In October, 1862, he went to Havana in a Spanish

man-of-war, the Blasco de Garay, and after remaining there a few weeks he

sailed for Cadiz. From there he went to Paris by rail, where he remained until

the spring of 1865, when he returned to New Orleans. In 1867 he again went to

Paris and remained about eighteen months.

During the ten years following his return from Europe in 1859

Morphy's practice of chess was limited to casual games with intimate friends,

chiefly with Charles A. Marian of New Orleans and Arnous de Riviere of Paris. It

is thought the total number of games played during these ten years would not

exceed 75. The completeness of his abandonment of the game may be inferred from

the fact that although the great International Chess Tournament of 1867 was

going on in Paris during his third visit to that city he never once visited the

scene of its exciting and splendid contests. Morphy played absolutely no chess

with anybody after the year 1869.

The mental derangement which overwhelmed Morphy's brilliant mind and clouded his

later life is a curious chapter in his career, and has given rise to no little

wonder among chess players as to the cause and conditions of his mania. Without

going into the details of his mental troubles, two conclusions stand out very

clearly, namely, that chess in no way contributed to it, and that the reverses

he experienced in his material affairs did. The latter conclusion is borne out

by the fact that his mania took the form of a delusion that his brother-in-law,

Sybrandt by name, administrator of his father's estate, had defrauded him of his

legacy, So intensively did this delusion dominate him that his perverted mind

conjured up machinations on the part of Sybrandt to poison him in order to quiet

his proposed action at law to recover, Morphy was perpetually in fear of being

poisoned, and as a precaution would eat nothing except at the hands of his

mother or his unmarried sister, Helena, This proposed action against his

brother-in-law absorbed Morphy's attention for many years; being a lawyer

himself he busied himself with the details of his suit, and was much about the

law courts in consequence. It should be stated, however, that Mr. Sybrandt

discharged the obligations of the trust entirely to the satisfaction of the

court, which is a matter of record.

It is difficult to fix the time when Morphy's mind was noticeable

unbalanced, When the second American chess congress was held in Cleveland in

1871 strenuous efforts were made to secure Morphy's attendance, but he

persistently declined all invitations that were urged upon him. Rumors of his

malady were abroad then ; some people who were in a position to know aver that

his mania was perceptible even before that date. Morphy was never legally

declared insane; he was so harmless and reticent, and lived in such quite

retirement at his home, that there was no need of putting him under any

restraint. In June, 1882, his family did endeavor to place him in a sanitarium

in the hope that he would be benefited. The institution was called the Louisiana

Retreat, located near New Orleans, and under the patronage of the Catholic

church. Those in the party that accompanied Morphy were his mother his brother

Edward, and his intimate friend C. A. Maurian. When they reached the asylum

Morphy protested against his detention with such evident sanity, and discussed

his civil rights with such a learned knowledge of the law, that the Sisters in

charge were afraid to assume the responsibility, and he was taken back home.

During all these years of misfortune Morphy still loved

chess, and kept run of the current news of the game down to his death. But he

was annoyed, and at times even enraged, at the mention of it. This may seem

rather contradictory but it should be remembered that his experience and

environments were peculiar. It may be worth while to relate an episode that

discloses Morphy's feelings. regarding chess better than anything else. Under

the pretense of assisting him with his suit against his brother-in-law, a lawyer

of New Orleans examined the papers in the case and gave his opinion in Morphy's

favor. He gained confidence to such an extent that Morphy ate a piece of rock

candy, first seeing that the lawyer himself had eaten a piece. The lawyer then

suggested that he would like, at some convenient time, to play a game of chess

with him. Morphy seemed alarmed; made sure that no one was in hearing, and then

replied : "I dearly love chess, but not now, not now - when we win the case."

When Steinitz was in New Orleans in 1883 he persistently tried to

see Morphy, and Morphy persistently avoided him. After four failures to effect

an interview between these two celebrated chess players, friends of Morphy

finally secured the promise to meet Steinitz on condition that chess would not

even be alluded to. This condition was adhered to, and the interview lasted

about ten minuses, but was mutually embarrassing on account of the forbidden

subject, When Morphy was first approached by a friend in regard to meeting

Steinitz, the remark was made that "Steinitz is in the city," to see what effect

it would have on Morphy, He replied: "I know it," and after a pause he

continued. "His gambit is not good." There is a world of meaning in these words

to one who is familiar with all the particulars to which the words may apply.

Morphy was then asked if he kept a board and men at hand to play over games, and

he admitted he did, but he could not be induced to talk further On the subject

of chess.

It is said by those most qualified to speak that Morphy's mutual

derangement did not impair his chess powers in the least; that at any time

during his later years he could have played with all his pristine brilliancy and

accuracy.

When Dr. Zukertort was in New Orleans in 1882 he met Morphy on Canal

street and handed him his card. Morphy put the card in his pocket without

looking at it and then greeted the doctor by name speaking i n French. Zukertort

was amazed, and exclaimed: "Why, how is it you know my name without looking at

my card? And how did you know I speak French?" Morphy satisfied his curiosity by

remarking: "I met you in Paris in 1867, and you spoke French then."

Paul Morphy died suddenly at his home in New Orleans July 10, 1884.

He had indulged in a long walk during the heat of the day, and on his return

home went to the bath room to bathe. It is supposed the shock of the cold water

on his overheated body caused congestion of the brain, for he was found dead in

the bath tub shortly afterward,

After his death his trophies were sold at auction. The silver

service, consisting of a pitcher, four goblets and a salver, being the first

prize won at the chess congress, was bought for $400 by Mr. Samory at New

Orleans; the set of gold and silver chessmen was taken by Walter Denegre, acting

for the Manhattan Chess club of New York, price $1,500; and the silver wreath

sold for $250, also bought by Mr. Samory.

An engaging pastime of chess writers and critics of late years has

been that of comparing the latter-day masters with Morphy, but so far the most

flattering comparisons have never exceeded that of equality with the immortal

Morphy. None have claimed that he has been surpassed by his successors. It is

safe to venture the opinion, however, that a great majority of chess players

award Morphy the palm of superiority over players of all times. Certainly,

taking into consideration the fact that he was in no sense a chess student, that

he regarded the game solely as a pastime and himself as an amateur; not

forgetting his extreme youth when he achieved his wonderful victories, nor the

fact that his chess career covered a period of less than two years -remembering

all these facts in addition to his sublime chess play and then comparing him

with the seasoned veterans of the checkered field, who have devoted years to the

analysis and practice of the game, it would not seem beyond the bounds of

moderation and reason to regard Paul Morphy as the greatest chess player that

ever lived. return |