|

As most people know, Paul Morphy received

his L.L.B. degree on April 7, 1857. Since this was shortly before his 20th

birthday, he was to young to be admitted to the bar. It would be another year

and two months before he could begin practicing law. While he

would have begun practicing law in June of 1858, he found himself, instead,

setting foot in England, starting his phenomenal and legendary conquest of the

European chess world, making himself a national hero in the process - and almost

totally destroying his nascent legal career plans and pushing his hitherto

charmed life down an inconceivable and contradictory path.

Neither Regina Morphy-Voitier nor Leona Queyrouze Barel, who gave us the best

personal glimpses into Morphy's life, had much to say about Morphy's legal

career. Since neither of them knew him at that time, this is understandable.

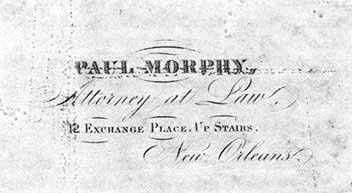

Very, very little is known about Morphy the lawyer. The business card (on the

right) testifies that Morphy did set up his own law office at 12 Exchange Place.

Philip Sergeant was under the impression that this was in 1862, and closed

because Morphy decided to spend the war years in Paris. David Lawson maintains

that Morphy never attempted to set up shop until after he returned from Paris in

1864:

Elsewhere [e.g. p.26, Morphy Gleanings] it is

stated erroneously that he opened a law office soon after

his return in 1859, but this (1864) was his first time

to establish himself at his profession.

Both Lawson and Sergeant claim that Morphy closed shop after

just a couple months, but neither of them offered any substantiation for any of

their assertions.

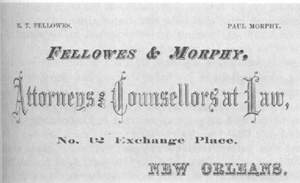

According to Lawson from about 1872 to 1874 Paul Morphy partnered with

established attorney E. T. Fellows. Most information about this venture is

speculation. Morphy's aversion to discussing chess would have made any public

profession difficult at best. The extent of his involvement in this firm is

unknown. 12 Exchange Place seems to be a common thread that could

lead to a lot of conjecture, but nothing, so far, is known about Morphy's

connection to that address. In a letter to

the New York Sun, May 2, 1877, Charles A .Maurian explained:

[Morphy] is now practicing law in this city, and has never

been insane, or spoken of in that relation by his family or friends. As to

chess, he is unquestionably to-day the best player in the world, although he

does not play often enough to keep himself in thorough practice. He gives

odds of a knight to our strongest players, and is seldom beaten, perhaps

never when he cares to win.

This demonstrates that Paul was doing some sort of legal work,

and playing chess, as late as 1877.

Lawson further wrote:

"Whatever activity Morphy engaged in other than chess during

the years 1865 through 1866, we know not. Nothing is known of his legal work

for clients, if he engaged in any."

However, sometime between August 9, 1864 and July, 1867 (when

Morphy left for Paris, via Cuba) Morphy, acting as curator ad hoc,

represented a client in a civil case before the Louisiana Supreme Court. The

case, an appeal, was decided upon in November, 1867. Since Morphy was in Paris,

it's apparent that the case was argued, either orally or through written briefs,

prior to July of 1867. Morphy's client, A. Dhones, who was the defendant in the

original case which was won by the defendant, had the original judgment upheld

in the appeal (the appeal was denied).

Therefore, sometime between August 9, 1864, when the original

suit was filed and July of 1867, Morphy was practicing law in New Orleans.

The appeal summary is presented below

Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Louisiana.

pp.503-

NEW ORLEANS, NOVEMBER, 1867.

[Chief Justice: Hon. Wm. B. Hyman

Associate Justices: Hon. Zenon Labauve, Hon. J. H. Ilsley, Hon. R.

K. Howell, Hon. J. G. Тaliaferro ]

Bellocq vs. Dhones and Penent.

No. 823.—H. BELLOCQ v. A. DHONES AND A. PENENT.

Plaintiff sues defendant for a settlement of the partnership account, and for

damages against the managing partner. A third party intervenes, and claims a

schooner as his own property, which he had purchased from the defendant, the

managing partner, by notarial act, prior to the institution of the suit.

Plaintiff remets his demand on the grounds, 1st: that the act of sale was not

recorded, as required by acts of Congress; 2d, that it is not expressed on the

face of the act of sale that he acted for himself and partners ; 3d, that the

price was not a good one, and the purchaser had notice of the claims of the

other partners. The notarial act of sale, which informed the intervenor of the

interest of plaintiffs, also informed him that the legal title was in defendant,

and that the defendants have full authority to sell the vessel: Held— That,

under the terms of this agreement and authority, the transfer of the schooner,

by defendant to intervenor, of the legal title, carried with it the equitable

title also.

APPEAL from the Sixth District Court of New Orleans, Duplantier, J. G. Schmidt,

for plaintiff. C. W. Hornor, for intervenor. Paul Morphy, for curator ad

hoc.

HOWELL, J. [Probably Justice R. K. Howell] This is a suit to dissolve a partnership, sell and

distribute the proceeds of a vessel belonging to the partnership, and to recover

damages from the managing partner for negligence, unskillfnlness, etc.

One of the defendants, A. Penent, joins the plaintiff in his

demand. The other is represented by a curator ad hoc.

The only question before us is raised on the intervention of

Christoval Espinóla, who claims the vessel as owner, by purchase for a valuable

consideration from the defendant, A. Dhones, as sole owner, and having the right

to sell.

By a notarial act between the parties, Dhones, Bellocq and Penent,

it is declared, that they are the joint owners of the schooner Glacier, bought

and registered in the name of A. Dhones, who is appointed master, and vested

with authority to sell, at his discretion, for " a good price."

On the 9th of August, 1864, he sold to the intervenor, by act, acknowledged

before J. M. Day, Notary, and on the next day this suit was filed, and the

schooner sequestered. Plaintiff, who alone complains of the judgment, contends

that the title of the intervenor is not good, because it was not recorded as

required by act of Congress, July 29th, 1850, (Stat. at Large, vol. 9, p. 440;)

because there was no delivery; because it is not expressed on the face of the

act of sale, that Dhones acted for himself and his partners; because the price

was not a good one; and because the purchaser had notice of the claims of the

other partners."

We consider it necessary to examine the third and last grounds only, which may

be thus stated:

The intervenor, having knowledge through his agent, that Bellocq &

Penent were partners, the act of sale to him by Dhones, in whom the legal title

existed, should have expressed that he acted under his mandate in selling their

interest.

The rule invoked by plaintiff is undoubtedly correct: "Nothing is

better settled than the rule, that the purchaser with notice of a trust stands

in no better situation than the seller, and it is equally settled that notice to the agent is notice to the principal."

But this rule, as quoted by plaintiff, appears in a dissenting

opinion, and was not considered by a majority of the Supreme Court of the United

States, to apply to the case decided, which on this point is quite similar to

the one now before us. See 2 Black., page 372. The notarial act which informed

intervenor of the interest of Bellocq & Penent, also informed that the legal

title was in Dhones, and that the latter had full authority to sell the vessel.

Under the peculiar terms of this agreement and authority, the transfer by Dhones

of the legal title carried with it, in our opinion, the equitable title. The

proof adduced by plaintiff of knowledge in the intervenor of his rights, is also

proof of his authorization to transfer those rights, which were carried in the

name of the transferrer.

The evidence does not satisfy us, that the District Judge erred. It

is therefore ordered that the judgment be affirmed, with costs.

Rehearing refused.

|